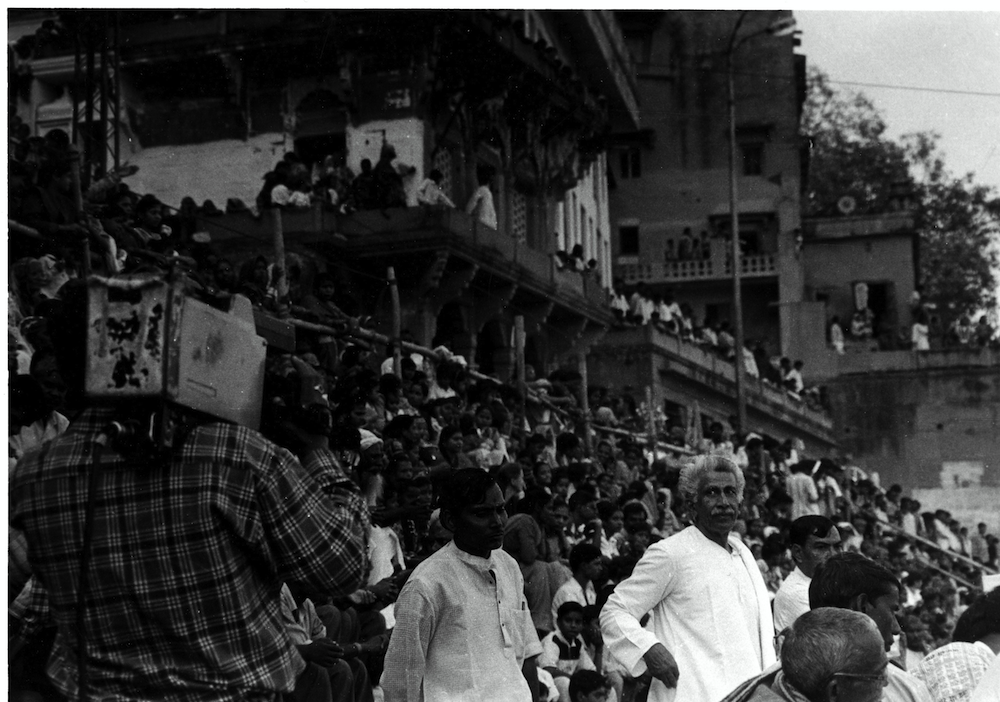

Veer Badhra Mishra, at the Krishna Lila, Tulsi ghat, Varanasi, 1997.

Veer Badhra Mishra, at the Krishna Lila, Tulsi ghat, Varanasi, 1997.

I was saddened to hear the news this week of the death of Mahantji’s, and it led me to dig out the picture of him at his beloved Krishna lila and the following which I wrote for a collection about him late last year. The news item from the Times of India speaks to his international and national profile. The following is more of a personal reflection of my memories of him.

I came to know Mahantji when I lived in Varanasi between August 1996 and December 2007. I had the good fortune to find lodgings with his maternal nephew and through these connections was able to experience Mahantji’s work and influence on the neighbourhood, the wider city and his extended family.

Often I would end my day by visiting Mahantji in his ‘receiving room’ at Tulsi ghat. Having wiped my brow and removed my gamcha I would be ushered in, to be greeted by a picture of serenity, far removed from the hustle and bustle of the streets. Of course I was never alone for these audiences. More often than not there were other supplicants and visitors keen to discuss various matters with Mahantji and I was always struck by his kindess with his time and his willingness to listen to people’s problems or points of view. Indeed his ability to listen before making a judgment or offering advice was never lost on those who had sought his opinion – even if, as often seemed the case, they didn’t hear what they would have liked from Mahantji, for he did not suffer fools gladly.

I think the strongest impression I have of Mahantji is his generosity. Much of what is written about him and his work focuses, quite appropriately, on his work to find a permanent solution to the on-going pollution of the Ganga. However, Tulsi ghat always struck me – and I use the word struck advisedly – as the centre of a project of cultural patronage. The cultural and religious intensity of Varanasi is in large part the result of the spiritual and financial investments of people such as Mahantji whose patronage provides the basis for some of the most signification events in the religious and artistic calendar of the city. I’m thinking especially of the Krishna lila (play), the Sankat Mochan music festival and the countless other festivals, such as the Dhrupad mela, and events which, with his financial and spiritual support, mark out the cultural rhythm of the city. The crowds at these events make it clear that these are not minority interests, even in an era when mass media (my object of study during my years in the city) compete for their attention. The cultural intensity of the city is in large part due to the leadership of people like Mahantji whose acts of patronage provide the basis for much of what has, over may centuries, made Varanasi a distinctive city with a undeniable performative richness

Many of the guests at Tulsi ghat had travelled from far beyond the city to have their audience with Mahantji. Academics, journalists and those interested in his work on cleaning the Ganga were often to be found in attendance. These guests often seemed fascinated by contradiction presented by a professor of Hydrological Engineering committed to the cause of the Ganga’s pollution, and a devout Hindu who would bathe in its pure waters each morning. It always struck me that there was little point in trying to understand Mahantji in terms of this apparent contradiction because for him there is no tension in the idea that one can be a devout Hindu and an engineer. Instead we can see that his life’s work was devoted to one substance – water – that is at the heart of the beliefs and daily practices of Hindus, and his beloved Varanasi, and is the ultimate sustainer of life on earth. In that sense Mahantji’s work and life transcends distinctions between the secular and the spiritual, or the worldly and other wordly. His life was one of profound unity.